Tell us about your path to becoming Executive Art Director at Britain’s leading independent publisher, Walker Books.

I haven’t followed a complicated career path.

I ended my education by graduating from a Fine Art MA, and hoped to make it as a painter and set up a studio practice. However whilst I was studying I had been freelancing on and off at Walker Books, doing a little basic design work and getting what amounted to an apprenticeship in book design under the tutelage of Walker’s Art Director, Amelia Edwards. Amelia is an astonishingly good book designer and an inspired Art Director, and I was very fortunate to have the opportunity learn from someone like that. As time passed, I became less and less of a painter and more and more of a book designer, until I ended up where I am now. I’ve never worked at another publisher.

At Walker, who are the key people responsible for the overall vision of a children’s book?

The author and the illustrator.

In fact I think that there’s something very wrong if the overall vision for a book comes from any other source. Of course, a good editor and designer may play any number of important roles – asking useful questions, giving advice, critiques, encouragement, and occasionally coming up with a bright idea or two. But the book has to belong to the author and illustrator, anything else doesn’t make any sense as far as I’m concerned.

What kind of opportunities does working on children’s books present when compared to other areas of publishing?

I get to work with a large number of astonishingly talented illustrators. The quality and range of work that finds its home in the field of children’s publishing is staggering. It’s a delight to be able to work with so many talented people.

What are the advantages of working with illustrators who are also authors? Can you give us an example of a project you have art directed where this was the case.

One advantage is that there are never any arguments between author and illustrator! More seriously, the working process is often more fluid with an illustrator who is also an author. Big changes in the structure of the book can happen quite late in development.

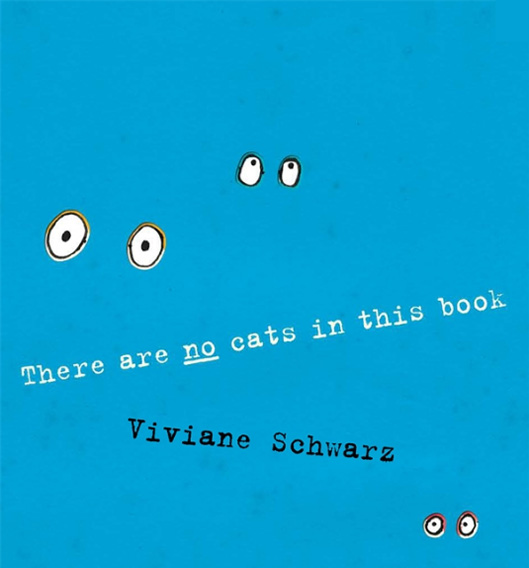

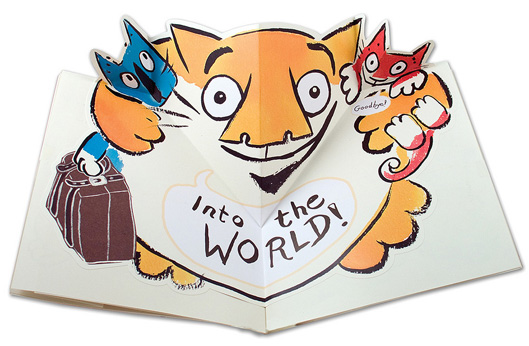

An interesting example of an author/illustrator that I’ve worked extensively with is Viviane Schwarz. Two projects which she has both written and illustrated (and I have been involved in) are the brilliant pair of interactive picture books,There Are Cats in this Book and There are No Cats in this Book. Working on these books involved long (and often pretty weird and philosophical) discussions between her and me and the editor, Lucy Ingrams. We would talk about about what the reader of the book might be thinking about the cats in the book, what the cats might be thinking about the reader of the book, and questions about where exactly the cats were, metaphysically and epistemologically speaking, in fictional and actual space, both in the book (and out of it). This sort of discussion became part of the way that Viv developed the books. It was quite loopy, and enormous fun.

How should a great dummy book be presented?

If the potential of the book is great, then frankly the dummy doesn’t need to be especially amazing. I would be impressed by a black and white sketch dummy (that wasn’t too fancy or finished), one sample piece of finished art, and a sheet or two or really well developed character studies for the folks in the story. That last item is something you don’t see so often, but it really does make an enormous difference in getting an understanding of what an illustrator’s potential might be.

Talk us through the making of one of Walker’s most recent children’s books.

Each book is has a very different history and I’m afraid I find it hard to choose one to talk about in particular.

Generally, most books will go through an early development period, when the creators will be working exclusively with one editor and one designer. This will probably be before contracting the book. During this period we like to chat a lot about the books we’re working on. Also, we read the texts out loud a great deal. This bit of the process is usually a lot of fun.

Once a fair bit of this development work is done, the editor and designer will present the project to a bunch of other folks in the company. If everyone is excited then we’ll issue contracts. At this point the illustrator will start making the final pictures and the designer will work with them to tie down the final form of the book. Most of the time, if anyone has an interesting design idea at this point, then it’s a matter of trying it out and seeing if it works. Design is basically experimental practice.

Eventually the book will get to the stage of final proofs. By now, the designer and illustrator should have a lot less to do and most of the action will have moved over to the sales team. Normally it’s at this moment that the illustrator and I should be getting our heads together about the next book!

Has the role of Art Director changed much since you first stared in this industry?

Not really, not in regard to the important stuff (but as you now know from my very first answer, I have a very narrow experience of publishing houses). All kinds of technical aspects of the job have changed – for example, when I began learning about publishing, computers didn’t figure in any way in the business of book design. But the main thing about art direction is the ability to communicate cogently and usefully and helpfully to people (be they illustrators, authors, designers or editors) about aspects of design. The need for and the nature of those particular skills hasn’t changed at all.

What is your favourite Walker Book currently on sale?

There are too many to list! And I refuse to be drawn on the subject of favourites.

However, if you’re asking me to recommend some Walker titles (apart from those I have already mentioned), here’s half a dozen illustrated books that I think are excellent: Penguin by Polly Dunbar, A Bit Lost by Chris Haughton, A Place to Call Home written by Alexis Deacon and illustrated by Viviane Schwarz, I Want My Hat Back by Jon Klassen, A New Year’s Reuninion written by Yu Li-Qiong illustrated by Zhu Cheing-Liang, Gum Girl by Andi Watson.

More generally I would say that the things which typically draw me to an illustrated picture book are: great characterisation; a sense of humour; great characterisation; impeccable timing; great characterisation; a real emotional hit to the work; oh, and great characterisation.

You have worked on a multitude of publications, from teen fiction to pop-ups and from board books to graphic novels. Which genre has been the most interesting to work on and which formats are the most challenging to art direct?

A book is usually as interesting and as challenging as it’s contents make it. The particular genre is really not that important. Very young novelty titles often seem hard to me because when they’re done well, the results look quite effortless, which hides all the thinking that’s gone on under the surface. YA fiction covers always have a lot riding on them, as the cover has to represent an entire (and usually very complex) book. This is, of course a completely impossible task. So the cover has to be a kind of massive simplification of the book’s tone and message, something which is also very hard to do well.

Ultimately though, the most interesting books to work on are the ones made by the most interesting authors and artists.

In your opinion, what makes a children’s book a global success?

Goodness knows!

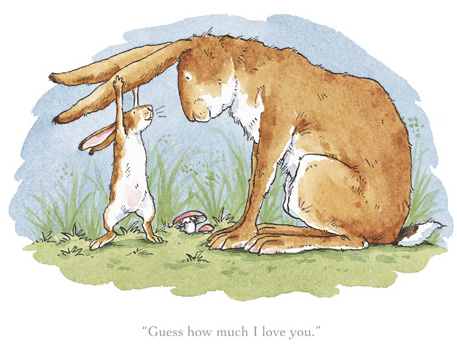

Often big universal messages seem to have a global reach. An example of that is Guess How Much I Love You by Sam McBratney and Anita Jeram. However it’s worth pointing out that it’s wholly impossible to say which books will be big successes in advance of the fact of their success. For example, when Walker Books first published Where’s Wally, (by Martin Handford) everyone at the publisher knew it was an extraordinary book, but no one could have predicted it’s success.

In a way, that’s all a publisher can do – endeavour to deliver potentially extraordinary books, either by pursuing excellence, or innovation, or occasionally just publishing things that are completely bonkers. Somewhere in amongst all of that will be found the books that will endure.

This interview has been syndicated courtesy of Childrensillustrators.com