Explain a little about your career so far at Mother Jones – what does your role entail and what have been some of your significant achievements with the magazine to date?

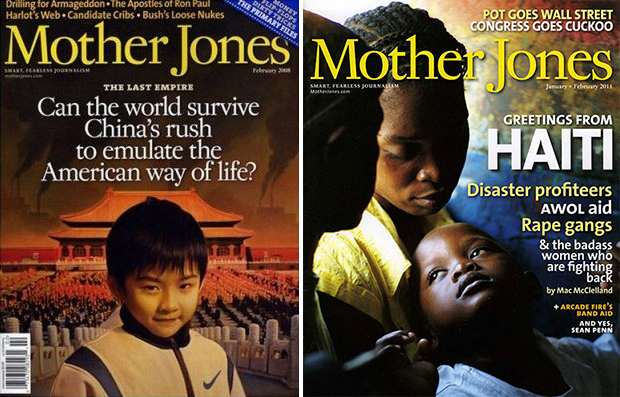

I started at the magazine as the photo intern (a position we no longer have) in 2007. I’ve worked to maintain a strong photo presence in the magazine, pushing to get great photo essays published as often as possible. I’ve also built a relationship with the Magnum Foundation to provide an outlet for some of the work they’re funding. It’s great to be able to provide a platform for important stories that get a little bit of funding. Funding a story doesn’t matter much if the piece never gets published, if people don’t get to see the story. On a personal level, I’ve gotten to meet and work with a lot of amazing photographers. I like being able to give an outlet (and money) to photographers who I think are doing some of the best work today. Of course, there’s a lot more I’d like to be doing, a lot more work I wish we could publish.

Mother Jones has a great reputation for publishing boundary-pushing photo reportages. Tell us a little bit about the ethos behind selecting work for publication in the magazine.

We get a lot of great proposals for photo essays, but have precious little space to run them. It’s tough to turn down so much great work; it’s also tough to find just the right piece to run in the magazine. Beyond the basics: a concise story told well with photos, I’ve found that stories with a strong tie to issues facing the United States fit best in the magazine these days. Those can be US-based pieces or foreign stories that highlight an issue that directly impacts the US. Pieces that present a new, different or unexpected take on well-known issues are good. I guess there is not necessarily a central ethos to the work we select. It depends on what else is in the issue, what we’ve run in the past and it depends a lot on how well the story is told.

I get a lot of photo essays that either have a strong story, but the photos just don’t do the job of telling that story, or the converse, a strong set of photos that just don’t have a solid story behind them. I also see a lot of photo essays that suffer a bit from sprawl. They might work well as a multimedia piece or a book, but we just can’t get the story told in the 4 – 8 pages we typically have for photo essays.

I see a lot of photo essays that just rehash well-trodden ground, telling the same stories over and over. It’s important to know what other work is out there, what has been published in Mother Jones, but also what other magazines have published. Even if your work is better, if we just ran a similar story to what you’re pitching, or if National Geographic or Time, Harpers or New York Times magazine just did the story, I generally can’t touch it.

You publish work often covering difficult subjects, with graphic imagery. What has been the most difficult editorial decision you have had to make?

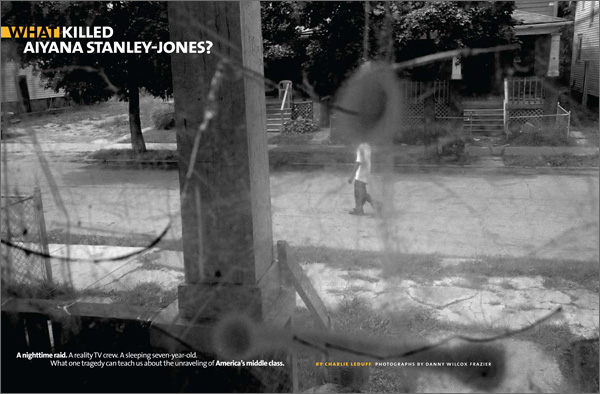

With Danny Wilcox-Frazier’s piece on Detroit (Nov/Dec ’10 issue), he photographed in the coroner’s office and got some really powerful images. Of course, some of the images were incredibly graphic. We had one image in layout of a body being autopsied. You have to weigh how much the image does to help tell the story. In that case we decided not to run the image, partially because you could see the person’s face. More than photos being too graphic though, we run into situations a lot where we need to photograph people who don’t want to be identifiable (undercover agents, vigilantes, children whose parents have dangerous jobs). We joke around here that if you can make a portrait of someone without being able to recognize them, that’s a sure in to getting work from us. Sometimes we decide to pull photos because, though the subjects feel okay with being photographed, we don’t want to risk compromising their safety by publishing the photo.

As a photographer you have shot some beautiful images covering not only hard-hitting global issues but also intimate behind the scenes photos of the US’ independent music scene. What for you makes a great image, and what is your favourite image that you have taken?

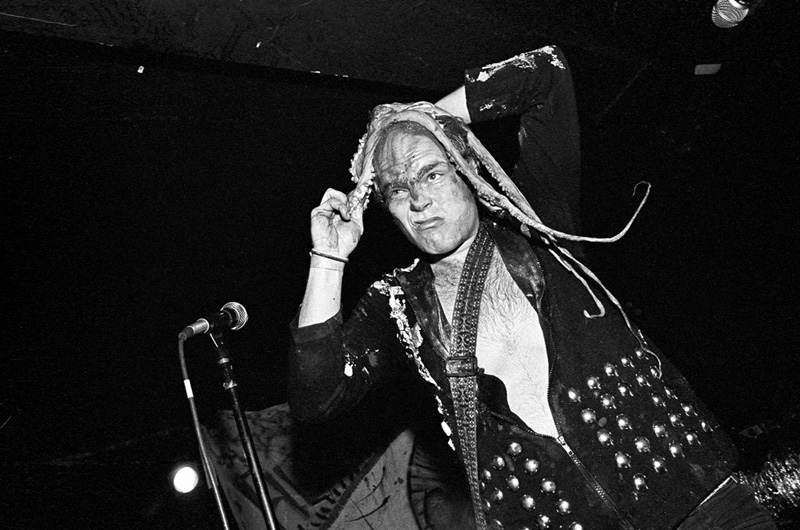

Thanks, I appreciate the compliment. I have a handful of favorites. I like the photo I took of a couple on New Year’s Eve, in San Francisco. I really like this one photo, of this guy Tyson lighting a cigarette. Both were such quick, grabbed moments. There are some band photos I really like, partially because they were great shows, great tours and evoke good memories – the shot of the Japanese band Teengenerate, the shot of Jay Reatard from the Reatards, Timmy Vulgar from Human Eye with the octopus on his head, my friend Vince rolled up in a carpet, sleeping on tour. Lots of favorite music photos. It’s funny, a few of my favorites don’t really make it into a portfolio or anything, but I love the photo. A good example is this photo I took in Kiev during the Orange Revolution. It’s just a really foggy shot of buildings, but I love it. Kind of a squishy photo that, for me anyway, is as much about a feeling of a place as it is about anything else. I have a few favorites that are like that: A street shot I took in Flatbush Brooklyn on a really hot summer night, coming out of the subway. A group of Italian sailors, one of them offering a cigarette. A shot of the Superdome in New Orleans shortly after Hurricane Katrina. Those are photos that kind of hit on the work I’d like doing more.

As for what makes for a great image, that’s so subjective and really depends on what the photo is trying to do. I feel like a really great image works on a less tangible level – it hits emotionally, it resonates in a way that makes you keep coming back to it. Photos that do that, whether they’re totally in your face or very subtle, are what makes photography so powerful and why I believe still photography remains one of the most effective mediums available.

Which photographer(s) that you have worked with do you most admire and what photographer(s) would you like to work with in the future?

I love working with Danny Wilcox-Frazier. His shooting style really resonates with me, and he’s a Midwest guy, like me. I love his work and he’s great to work with, which goes a long way. Chris Buck is a genius. I really appreciate his sense of humor, how it can be subtle, but perfectly on target. I wish we could work with him more. Those are two people who are at the top of their game, who I feel lucky to get to work with. There are more, of course. I just got to work with Stacy Kranitz on an assignment in Kentucky. She was great, she delivered so many really great photos, just nailed the assignment – likewise, Tristan Spinski. I’ve known him longer than just about any other photographer – we went to school together. It’s been great to see his work take this exponential leap to another level, from being a solid newspaper shooter to being a really great photographer, still on his way up. Zack Canepari’s work with Claressa “T-Rex” Shields is incredible. Lianne Milton was our go-to Bay Area photographer until she moved to Brazil. She’s great to work with and is making amazing photos in Brazil. Justin Maxon is a seriously talented photographer. I love what he does with his work, pushing boundaries. It’s always a treat to work with Matt Eich. I’m lucky to get to have a good amount of leeway to work with some of the best emerging photographers, as well as some real heavyweights, people whose work I’ve admired for years.

But there are a lot of other photographers whose work I wish we could have run. They brought projects to us that, for one reason or another, we couldn’t run. That’s such a hard part of my job, having to turn down excellent work. As for photographers I’d like to work with, there are tons. A few off the top of my head: Mustafah Abdulaziz, Carolyn Drake, Matt Black, Balazs Gardi. I’d like to work more with the photographers at NOOR. Stanely Greene is a favorite. They’re all really great. I’d love to get to assign something to Wayne Lawrence. He’s a brilliant portrait photographer. So many people I’d love to work with. I don’t know how it would make sense to work with him here at Mother Jones, but I love Morten Anderson’s work. It’d be awesome to do something with him.

You have experienced the industry from both a photographer’s and a picture editor’s perspective. How much do you think one informs the other, and which for you is the most rewarding?

They definitely inform each other. When I started this job, being a photographer helped me jump in right away. I had never worked as a photo editor prior to working at Mother Jones, but I knew photographers and agencies and generally had an idea of how things worked, from being on the other side. And being a photographer makes me much more tuned into the issues facing photographers with whom I’m working. I always try to be up front and honest with the photographers and get them as much money as I can for an assignment. I think the whole negotiating over fees and stuff can be such bullshit. Editors typically have a solid idea of what their budget is for an assignment. Almost any photographer can really usethe extra $150, $200, $500 that some editors try to whittle out of the invoice. Why screw around with stuff like that? On the other side, I’ve run into a few photographers who, no matter what fee I offer, they come back wanting more. It’s what they’ve been trained to do. I tell them, straight-up,here is what I can offer, it’s as much as I can get you. And it is. If you can’t work within that budget, I will find someone else.

I also like giving photographers the freedom to do an assignment in a way they’re excited about. You’ll get better pictures. If you want to shoot film and can get the images in on time, awesome, go for it. And in terms of direction, the photographer is the one on the ground, they see what’s there, they’re meeting the people. I’m happy to give direction, and always give at least an outline of what we’re looking for, but I like hiring photographers for their vision, for what they bring to the table beyond just taking the picture.

On the other side of the desk, I feel like my job as a picture editor should influence me more as a photographer than it actually does. I am a horrible, horrible editor of my own work. And I have a hard time coming up with good ideas for projects to work on. My own work is pretty unfocused, kind of a mess. I’m an exceptionally harsh critic of my own work. I don’t have much time to really concentrate on my own photography. I still shoot all the time, but don’t have time to do anything with it or even to stop and really think about what I’m shooting. I shoot, develop, scan, constantly about six months behind in keeping up with my own photo work.

How important is it for you to discover and showcase emerging talent through Mother Jones, and what sort of things do you look for when reviewing portfolio submissions?

I love getting to work with emerging photographers. I know how hard it is to get a leg up as a photographer, so if the fit is right for the story, I like giving an emerging photographer an assignment. The photo credit and paycheck mean a lot in the first few years out there. Not that they don’t matter later, for more established photographers, but it’s just different for people earlier in their careers. That said, in the end I always look for the best person available for the assignment.

When I’m reviewing portfolio submissions, I often look at the personal work, if they have any. I look at the stories to see how they put together photo essay. Not as much for the editing, but to see if the pictures tell the story they’re trying to tell. I look to see if they have a unique point of view, or a voice. A lot of photography is good, it’s fine, but it’s like everything else, so something that stands out for having a particular, consistent style always gets my attention. If the person is shooting portraits, I’m looking to see who the people are, what their portraits say about the photographer. I see a lot of portfolios with portraits of people who essentially just look like the photographer’s friends. They may be great portraits, but I’m not sure how that person might handle a gruff militia dude who isn’t into the idea of being photographed in the first place, or an old black woman or anyone outside of the comfortable realm of young, beautiful people. And if I’m looking at a portfolio in person, it’s always instructive to see how the person responds to criticism and what questions they ask, if any.

What inspires your creativity?

Music. I listen to music constantly. It’s hugely inspiring. And other photographers. I know that’s not super special, but I’m constantly looking at photography, more than just for work. Sometimes it kind of pains me to look at other photographers’ work…it’s so good, and sometimes so simple, but still powerful. It makes me wish I shot more and was more focused or at least had more confidence in my own photography. Shitty photography also inspires me in a way… there is SO much bad photography out there, mediocre photographers who get a lot of work. That actually inspires me a lot, thinking, “If THEY can get work, I know I can!”

In your opinion, what have been the most significant changes in editorial photography, both negative and positive, over the past few years?

The biggest change has just been the shrinking outlet for printed photography. It’s made a huge impact on photography, or at least for photojournalism. And while the Internet has provided a vast platform for photography, in ways that just weren’t even imagined 20 years ago, having fewer paid, print outlets has impacted the kind of work being done. One thing I see is since there are more self-generated projects, without an editor and often without a concrete outlet, the projects tend to be a bit more sprawling, less focused or just amorphous. Less “Country Doctor” and more “Impressions of Kremmling, Colorado.” It’s not a bad thing, but I feel like the kind of stories being told with photography is changing, along with how the stories are told. There’s more emotion being brought into the story telling, and by that I mean photos that are blurry or double exposed or just less directly telling a story, that work more on an emotional level. There’s definitely more of an artistic bent, photojournalists thinking as much about hanging their work as having it run in a magazine. That just was not common in the past, the idea of photojournalist as artist. That has changed the nature of what stories are being told, how they are told with photography and what kind of photos are being made.

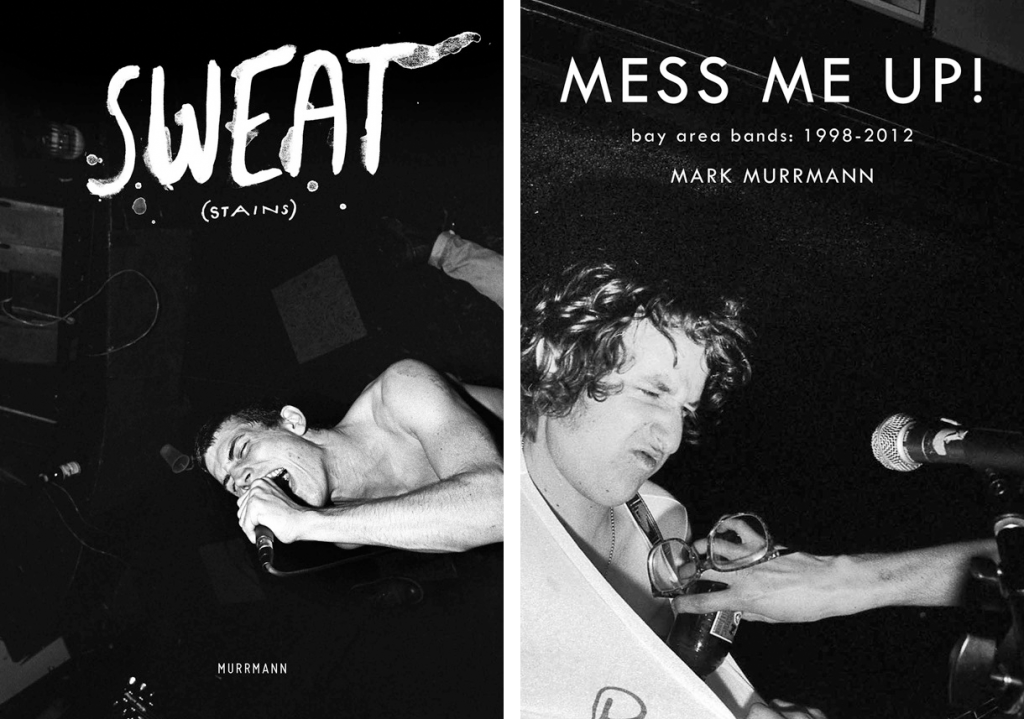

You have been involved in the punk and independent music scene for many years, having founded Sty Zine in 1991 and more recently the fantastic ‘Sweat (Stains)’, which acted as a retrospective of your punk photography. How integral are your experiences of being part of this scene, and the self-publishing of your magazine, to your development as a photographer in general as well as a picture editor for a large publication?

Well, it all adds up, all the experiences I’ve had self-publishing and being part of the punk scene and everything else. It’s made me fairly independent, or at least aware that there’s something out there beyond shooting for a paycheck, which I never want to do. That would kill my interest in photography. In terms of my development as a photographer, being part of the punk scene and doing my own zine in the ’90s turned me on to photography. I started taking (lousy) skateboard pictures and then pictures of bands that played in my basement. Taking those photos led to a job working in the photolab at the Indiana University School of Journalism, which is where I discovered

documentary photography, reportage, and photojournalism. It blew my mind. As for working for a large publication as a picture editor, my experiences I think help me connect with photographers and other people I’m working with on a more grounded level, person to person. Also I don’t feel the need to step on other people to get up in the business. Maybe I’m not pushy enough sometimes, because this is a business where it helps to have sharp elbows. But there’s no need to be a dick. I want to be the best I can be at my job, but not at the expense of others.

Portrait of Mark Murrmann © Ian Willms. Other imagery © Mark Murrmann, Danny Wilcox-Frazier, Mother Jones,